Cat and mouse

In the context of mobility, technology and beyond, it is important to remember that people are not rationally transactional. Products must not only meet a need, but also work around the quirks of human psychology. Our irrationality creates opportunities as much as it creates obstacles. Catering to it effectively takes a unique blend of creativity, adaptation and luck.

What is impressive about a good bundle is that it transforms reality: consumers are often happier for the bundle even if it encases an incongruity. Starbucks somehow established and globalized expensive coffee, getting people to pay a substantial margin on what was before an effectively commoditized product. Cities now have coffee shops selling expensive coffee everywhere, but coffee wasn't always something that made sense for consumers to pay extra for. What's even crazier is that even though a key part of why people pay a premium for expensive coffee is the in-store experience bundled with it, they're still willing to pay the same premium on packaged Starbucks coffee sold in a supermarket! Before Starbucks, Pepsi realized that consumers are more willing to pay a premium for soda than food, and so acquired chains of quick service restaurants as a channel to market for soda sales. It is weird to think of fast food as a loss leader to sell beverages, but soda makes a 90% margin and the low prices on food are what get customers through the door. The fast food and Starbucks empires have been built around the car, with drive-thru lanes to smooth the process of making these irrational purchases. The intersection between these things incidentally helps explain why America has a problem with obesity.

Trip pricing and its supply side efficiencies mean that mobility has a fundamentally better value proposition. These services are often fun, convenient and empowering, but habits are hard to change. Like a healthy diet, the trip economy needs to change perceptions in addition to underlying economics. Trip providers are therefore constantly playing a cat and mouse game to overcome consumer psychology in a rapidly evolving digital landscape.

Smartphones & apps

A smartphone puts trips in your pocket. Every new service has an app and the smartphone is the ecosystem from which they grow. In the process, it combines specialty mobility value propositions into a bundle that can substitute for the everyday mobility value proposition of car ownership.

While the smartphone is home to all of these value propositions, the way in which things are connected matters. Consumers don't like to download new apps while others are already deeply rooted. This digital ecosystem is like a jungle: occasionally a falling kapok creates space for new trees to grow, but for the most part it is easier for new branches to extend from already established stems. Successful apps with clear value propositions are like tall trees and new offerings that are looking to grow quickly can sometimes leverage these existing platforms.

Source: Our World in Data

About 5.2 billion people or two-thirds of all people on earth now have mobile devices and spend more than six and a half hours a day using them on average. Time spent on mobile is dominated by social media, messaging, video and gaming.

Source: App Annie

Apps where people spend most of this time are subject to a kind of gravitational force: if you use an app regularly you'll likely feel comfortable using it for more things, so long as these things are adjacent enough to the main thing you use it for. This plays out in a number of ways when it comes to mobility apps, some of which act like trees and the remainder of which act more like branches.

Trip bundle apps

The first rule of mobility app gravitational dynamics is that more trip types is better than less. Uber started with just Uber Black, but saw rapid uptake when it added UberX. Other ride types (like Uber Green) have been added over time, but more importantly, Uber Eats and the acquisition of Jump expanded Uber's app offerings beyond ridehailing into food delivery and micromobility. Uber has also incorporated public transit into its app and is now adding grocery and alcohol delivery with the acquisitions of Cornershop and Drizly. In the process, Uber is building an ecosystem of trip offerings rather than a tool for ridehailing alone. Uber has also leveraged its platform strength to aggregate other mobility apps into its ecosystem. For instance, in Paris you can find both Lime scooters and Cityscoot mopeds on the Uber app.

Lyft has followed a similar strategy, expanding into micromobility through the acquisition of Motivate (which operates bike sharing services like Citi Bike) combined with its own scooter offering. Lyft has also launched a car rental product. However, it has struggled during the covid pandemic relative to Uber because it lacks an offering akin to Uber Eats, which surged even as ridehailing collapsed. Lyft is now working to address this by launching a food delivery service.

Ridehailing isn't the only potential launching point for bundled offerings. Lime tried carsharing and Tier offers mopeds in some cities (it acquired Bosch's Coup subsidiary). Sixt, which faces competition from ridehailing products, has in turn launched an app in a variety of German cities that offers ridehailing, car sharing, car subscription and scooter aggregation in addition to car rental. Sixt, which has a relatively small US footprint, has also partnered with Lyft to support its car rental product.

In China, Didi has expanded into a much wider array of services than its US analogs. Beyond rides of various kinds (taxis, private cars, luxury vehicles, corporate services, pooled rides), Didi also offers bicycles, DiDi Bus, drivers that can be hired to drive your car, Hitch intercity carpool rides (which have faced significant issues) and DiDi Foodie food delivery. It's now moving aggressively into grocery delivery.

Mobility superapps

When a mobility app has sufficient gravity through utilization velocity, it can expand beyond mobility. Didi's offerings include financial services like vehicle insurance, loans and crowdfunded medical insurance.

This strategy was pioneered by Tencent and Alibaba. WeChat for instance is not only the default messaging platform in China, but also a payments wallet which supports a panoply of other services and applications. Sending money through red envelopes is an ancient Chinese custom that was leveraged to popularize a now ubiquitous payments wallet integrate into WeChat. Digital payments through e-commerce and messaging gained massive traction since much of the population was unbanked. A lot of Didi's early traction and its ability to outcompete Uber in China came through Tencent and Alibaba's app ecosystem (both companies were early investors), but it has internalized these lessons to build similar services into its own ecosystem.

Source: e-Conomy SEA (Google, Temasek, Bain & Company Report)

In contrast to China where messaging led the way, Southeast Asian mobility services were the first digital platform through which many customers started paying for things. To get a shared motorbike in Jakarta (colloquially known as an ojek), most people are willing to go to the trouble of giving cash to the corner store in exchange for credit on their Gojek app that can be used to pay for rides. But once you have this balance of credit on the app, you can use it to do your shopping and have it delivered, send something through the courier service function, pay a bill along with a range of other things.

Online payments in Southeast Asia are projected to rise from $1.4 trillion in 2019 to 2.3 trillion in 2025, with digital payments expected to increase 5x, driving a significant portion of the growth. GoPay reported $12 billion in transaction volume in 2020 and both Gojek and archrival Grab are actively investing and acquiring to support their digital payments ecosystems.

Source: e-Conomy SEA (Google, Temasek, Bain & Company Report)

The payments velocity through their apps allowed both Grab and Gojek to become popular payments wallets in addition to their broad mobility offerings. These wallets can be used in stores to purchase goods or to purchase mobile phone data and these actions are even gamified in the app experience as "missions". Financial engineering is used to deepen investment into the payments ecosystem, including by bundling various offerings into "promo packs".

Wallets also naturally feed into a retail experience in which you can pay through the app and fulfillment is carried out by the mobility network. Gojek includes an online store through which consumers can browse offerings which are presented with promotions and discounts.

The ecosystem even extends into games and digital fitness, hosted by partner services.

And messaging is also built into the platform, in a way that allows for payments and extensibility. In this sense, the evolutionary journey of these platforms is somewhat the opposite of WeChat's (ending rather than beginning with chat), but incorporates many of the same learnings.

Grab hosts a similar array of services with payments at the center of the ecosystem (there have been sustained rumors of merger discussions between Grab and Gojek). More exotic Grab offerings include hotel bookings, movie tickets, insurance and gift cards.

Grab is even expanding into healthcare, partnering with Ping An Good Doctor to allow appointment bookings and medicine delivery through the app.

This potential for mobility services to be the driver for the creation of massive new digital ecosystems is fascinating to track as it rapidly evolves. A key factor for the emergence of such superapps, beyond mobility serving as an entry point into digital payments, is that mobility services have relatively broad appeal in emerging markets given the low rates of vehicle ownership and the relatively low cost of labor, which makes delivery and ojek ridehailing relatively affordable. In other words, lower labor costs mean that CATs can recruit the staff that they need with relatively little everyday mobility demand side competition from DOGs. As autonomy, electrification and new vehicle form factors enable cheaper and broader mobility value propositions, some of the possibilities demonstrated by these superapps will likely be imported to more mature markets.

Financial engineering

Source: McKinsey

A core value of mobility apps, especially in emerging markets, is their ability to serve as a convenient mechanism for transacting. This potential to act as a payment wallet creates a foundation for financial engineering. Creative financing solutions have long been an important tool for selling vehicles and are also quite helpful for selling trips.

There are two variations of trip pricing being rolled out that seek to shift the value proposition closer to that of ownership by offering a variety of benefits in exchange for a larger commitment from customers.

- Access bundles: By paying up front, an access bundle reduces the marginal cost of each trip. Such offers often take the form of "passes" which you buy in exchange for waived fees. These bundles are structured as a once off payment or as a recurring subscription which covers the full or partial cost of trips or a specific aspect of the trip cost. For instance, DoorDash's DashPass costs $9.99 per month and waives delivery fees on orders above $15. Bird offers Ride Passes in specific markets removing unlock fees for a short period of time. Uber and Lyft have much more sophisticated offerings that cover a wide range of trip types. UberPass gives 10% off rides and waived food and grocery delivery fees for $24.99 per month. Lyft has partnered to create a similar offering: a $19.99/mo Lyft Pink subscription gives 15% ride discounts, 3 free micromobility trips, priority airport pickup in addition to waived GrubHub delivery fees and Sixt rental discounts.

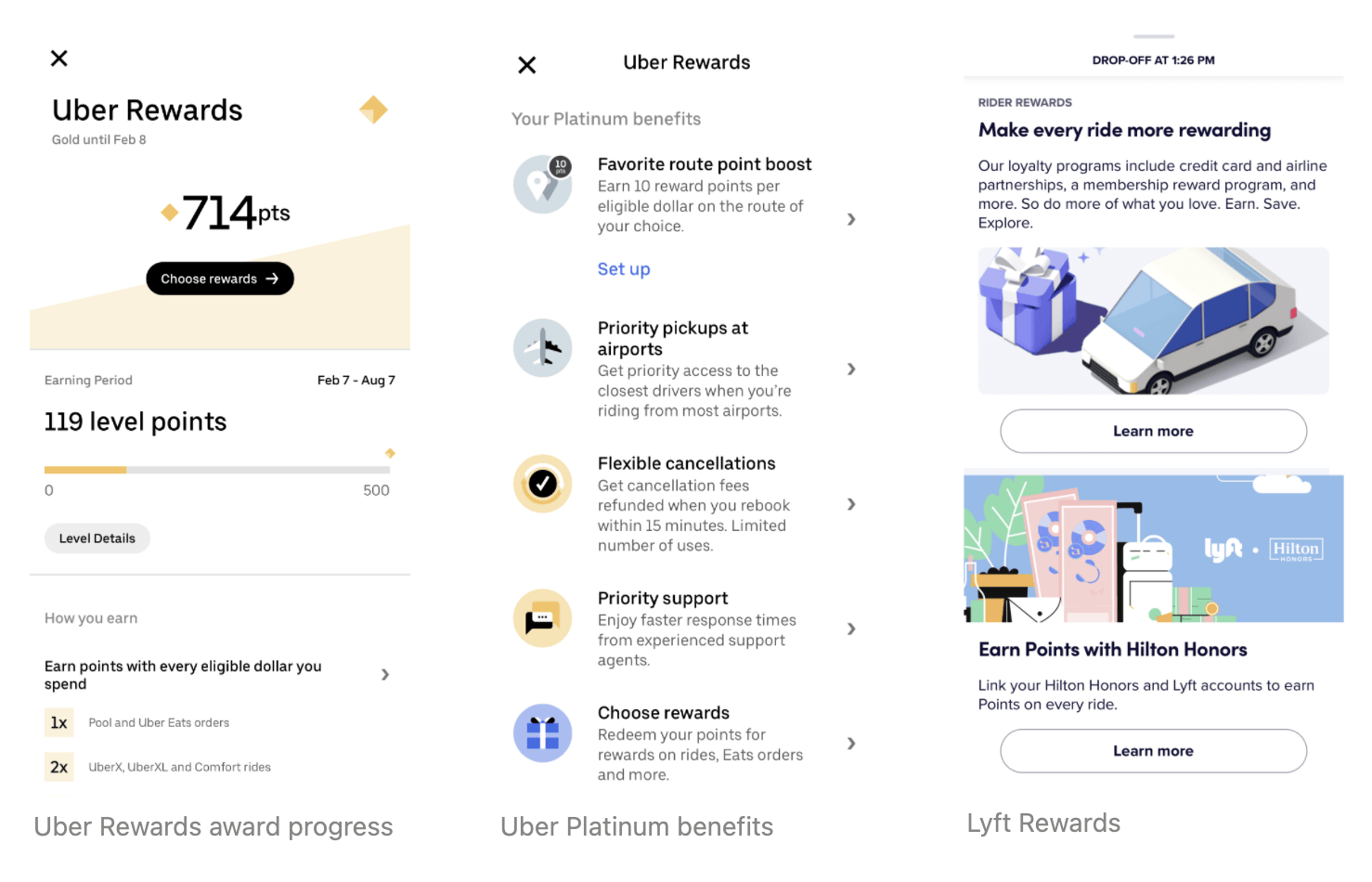

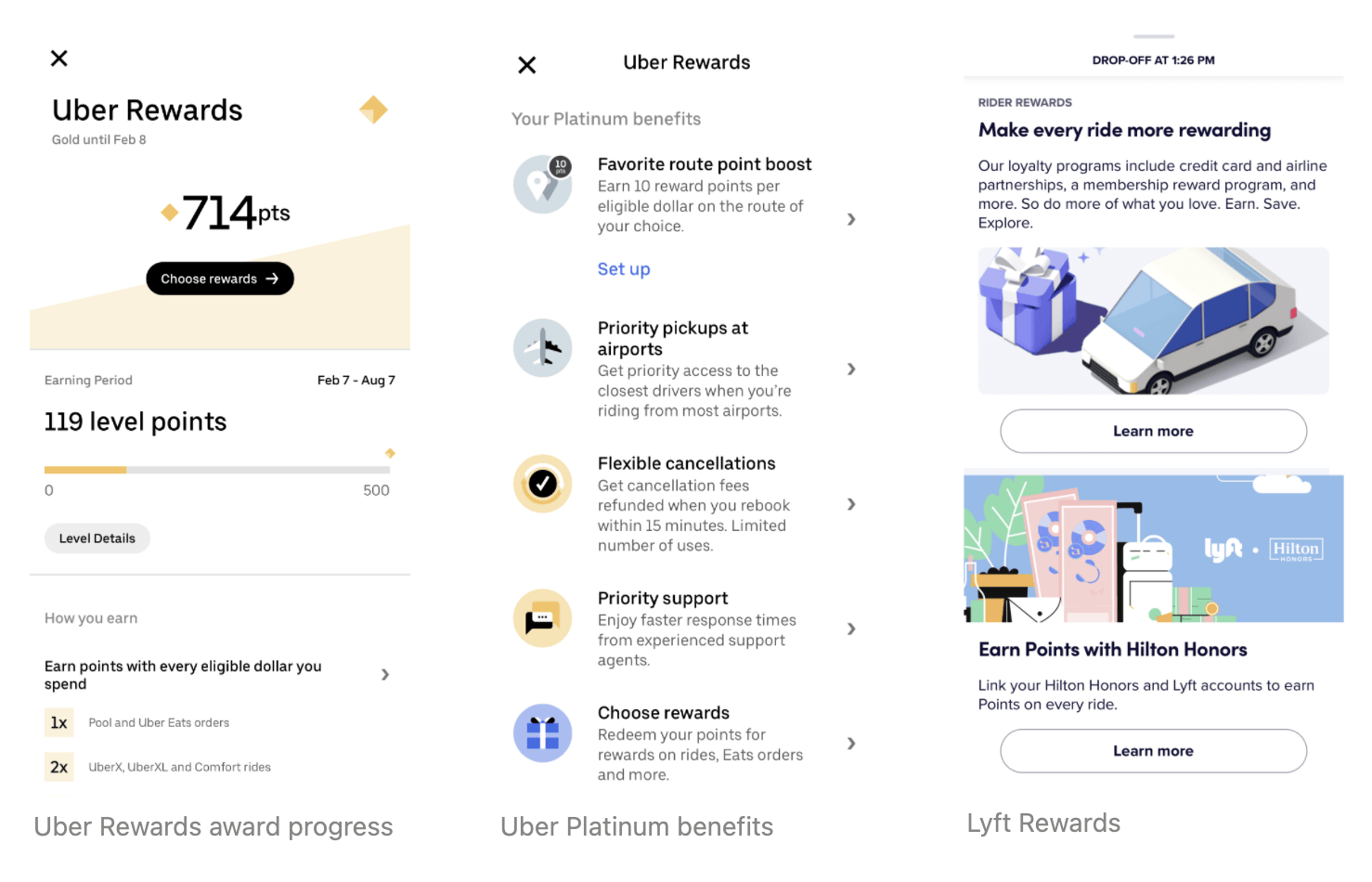

- Loyalty programs: In contrast to an access bundle, where you pay up front and get benefits after the payment, a loyalty program rewards users for using a service over time. The rewards, like airline status and frequent flyer miles, usually feed back into the program, either improving the quality of the service for the same cost or discounting future trips. There is usually also an element of social status signaling built in by creating graded tiers such as "gold" and "platinum". For instance, Uber Rewards has four status tiers: Blue, Silver, Gold and Platinum, with each successive tier offering additional benefits such as flexible cancellations and Premium customer support. The Uber Rewards equivalent of frequent flier miles is UberCash which can be recycled within the Uber ecosystem to pay for rides or food delivery. Lyft Rewards is similar and built around partnerships with Delta, Hilton and credit card providers.

In addition to creating their own internal financial incentives, mobility apps can link into the branches of broader payment ecosystems. As mentioned, this was a key aspect of Didi's growth, leveraging Alipay and WeChat as ways to pay in addition to demand sources.

The trip economy could also link to existing payments infrastructure through widely used public transit payment systems such as London's Oyster card or Hong Kong's Octopus card. This kind of integration would allow regulators to collect data and subsidize externalities, especially when trips link into the transit system (e.g. using a scooter to reach a subway station). Access bundles are already used as a way to pay for transit within a defined geography (think zone passes) or time period (e.g. day pass, transfers within a designated period) and offer a natural pathway to link trips with public transit.

Employers are another financial input into transportation decision-making. Companies have long subsidized the cost of getting their employees to and from work. This often comes in the form of a company car (which also covers the employee's needs beyond the office) and at the very least, free parking onsite at corporate locations. But parking is not free, especially in large cities, and companies with offices in high value real estate zones are starting to shift their transportation spending to other modes of travel. New forms of trips combined with payment bundles let companies reallocate transportation subsidies to other modes and they can do so more precisely given the nature of the trip economy.

Retail

Source: BCG

As we've seen, mobility superapps integrate e-commerce offerings. But e-commerce apps are powerful ecosystems from which mobility naturally extends. They not only incorporate payments but are already a key part of the trip economy even if they haven't been thought of in this way. And the ways in which they've grown give insights for other parts of the trip economy.

Fulfillment is the part of e-commerce that makes it a trip, but consumers hate paying for shipping. The clearest analogy to the general expectation of free shipping is the idea of free parking for cars. Of course, neither is actually free, but consumers often need to believe it for the value proposition to make sense. And in both cases, significant scale and organization is needed to effectively hide these costs.

This is the power of Amazon Prime: it is the preeminent example of an access bundle in action. It helped Amazon avoid what Eugene Wei calls an "invisible asymptote" or "product-market unfit" namely the point at which growth slows because the value proposition stops appealing to enough customers since they hate paying for shipping to "literally an irrational degree". By effectively pre-paying for shipping, "on some orders, and for some customers, the financial trade may be a lossy one for the business, but on net, the dramatic shift in the demand curve is stunning and game-changing."

Originally Prime meant free two-day shipping, but that has now come down to one-day shipping in many places. Some SKU-level wizardry is required to keep shipping windows optimally short: Popular items are identified and qualified while on the backend, the corresponding products have to be warehoused and fed into a distribution network that is constantly expanding and improving.

Amazon has also begun tackling adjacencies to e-commerce using Prime delivery as a key element of its attack. Specifically Amazon offers free two-hour delivery on groceries and essentials. Amazon originally launched this service as Amazon Fresh, but accelerated the rollout through the acquisition of Whole Foods, which gave it a physical retail footprint which helps strengthen the backbone of its grocery fulfillment network as its "first and best customer" for moving such goods. This is important because the delivery windows of shipping groceries are tighter and the logistical needs (including keeping items cool) are different. The acquisition of PillPack also allowed Amazon to launch Amazon Pharmacy and expand into delivery of prescription medication. It isn't hard to imagine Amazon expanding into other mobility verticals such as hot food delivery or even passenger trips, leveraging Prime to strengthen the appeal.

Amazon's main retail competitor, Walmart, has been forced to compete directly with Prime's core delivery value proposition, recently launching Walmart+, a bundle that is slightly cheaper but also skinnier. Walmart is likely to bulk up this bundle over time, but for now it includes free delivery "as fast as same day" as well as cashierless mobile phone checkout in Walmart stores and 5¢/gallon discount on fuel at Walmart affiliate stations.

What makes the Amazon Prime bundle particularly challenging for Walmart and others to compete against is how it is combined with an attractive media offering (Prime Video access, Amazon Music streaming and free access to a range of Kindle e-books). These are elements of commerce that Amazon absorbed as they became digital. Their virtual nature makes them fit well into a subscription bundle since their marginal costs are close to zero, helping to counteract the ways in which shipping costs scale more linearly.

Overall, Prime shows how effectively bundles can shift behavior towards trip modes when enough of the right elements are combined. But it also demonstrates how naturally Amazon and other e-commerce players could extend their ecosystem into new types of trips.

Maps

Maps are a search engine for physical space and are the ultimate mobility lead generation for outbound trips. That is to say, almost every time you open a map, you're considering making a trip. This makes maps a powerful trunk that naturally branches into mobility apps. Smartphone maps started by offering turn-by-turn navigation, which is still a key value proposition. But over time they've added public transit and Google Maps in particular has worked to incorporate other kinds of trips, including ridehailing, micromobility and food delivery. In some cases, it is possible to complete the entire transaction without leaving the Google Maps app. Google has also created APIs and integrations that help to route and manage a driver workforce.

Maps are hard to compete with since they have powerful network effects: as a map accumulates points of interest (POIs), the value to consumers grows, meaning more people use the map and add POI information - either passively by highlighting them through search or actively by filling in missing information - which in turn improves the map.

Trip operators face a tricky dilemma in choosing whether to integrate with maps: significant additional demand is hard to turn down, but it comes with the risk of aggregation. Looking further into the future, Google and Apple have invested significantly in autonomous technology and between them they own the two most popular mapping platforms. The viable alternatives are limited to HERE (owned by a consortium of German carmakers), TomTom and Mapbox. Similar dynamics exist in China where Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent own the leading mapping platforms.

Source: FT

It's noteworthy that Snapchat has a built-in map (powered by Mapbox) which allows you to explore what people are posting in particular locations around the world. It's also interesting how many of these videos show commutes. This is not to say that social media and mobility are particularly well integrated - Snapchat only lets you explore the world digitally through this map. But it is interesting to consider how mobility could tie our digital and real-world social interactions together.

While maps are about organizing information geographically, the social graph creates a different geometry: what matters isn't how far things are away in terms of physical distance but rather what are the human connections between them and how hard it is to bridge that gap. This is particularly relevant for social events: Facebook is where most people plan get togethers, so it shouldn't be too hard to tie trips into this loop. It doesn't matter so much where you're going as who you're going to.

This could extend in fun ways: in the heady early days of ridehailing, you could call an Uber through Facebook Messenger and there was an app called Bar Roulette that hailed an Uber to drop you and your friends at a random nearby bar. You could even send Snaps using an exclusive Uber filter en route. Those initiatives didn't last, but Bird and Bumble recently announced a more sober (though brightly colored) collaboration using decorated Bird scooters (which can serve quite effectively as outdoor billboards) to advertise the Bumble app, starting in Tel Aviv.

Messaging is of course also closely tied to all of this. Though platforms like WeChat are tied closely to mobility and payments, in the US and Europe messaging has tended to stay more siloed. As Facebook consolidates WhatsApp, Instagram and Messenger into a single backend and builds payments targeted at emerging markets into this platform, it seems that tie ins to mobility are likely to follow.

Social media